|

A seed may be defined as an embryonic plant in a state of arrested

development, supplied with food materials, and protected by one or

more seed coats.

It is able to remain alive, although dormant, through conditions

which may be unfavourable for immediate growth. When suitable

conditions occur a seed will begin to germinate.

Sleeping Seeds

|

Relatively few seeds will sprout as soon as they mature.

Even under ideal conditions most seeds remain dormant for what

is called a "rest period", which varies in duration

in different plant groups. Rest periods are thought to be

necessary for certain chemical changes related to the

"ripening" of the foods stored in the seed.

Seeds, though dormant, are living organisms and need

favourable conditions to grow.

|

How Long Do They Live?

Several factors contribute to the life expectancy of a seed. The

length of time a seed will remain viable (that is, able to sprout

strongly and produce sturdy seedlings) varies widely with the species

and the care taken in harvesting and storing the seeds. Some seeds

(e.g., chervil), rarely retain their germinating power longer than one

year. Other seeds, such as celery, cabbage, cucumber, and various

other vegetables and flowers, may sprout well when ten years old or

even more. Seeds not fully mature when gathered or stored before fully

dry, or kept at too high a temperature, may sprout very poorly or not

at all.

Travelling Seeds

Seeds vary widely in shape and size. The seeds of the begonia, are

almost dust-like. Seeds of the "double coconut" may be 30 to

45 centimetres long and have masses up to 20 kilograms. Seeds also

exhibit a marvelous diversity of form. In many cases the shape and

size of the seed is a special adaptation to assist in its

distribution. Some seeds, such as the "wings" of the maple

tree and the "parachutes" of dandelions and milkweeds, are

adapted for wind transportation. Other seeds use burrs and hooks, to

attach themselves to animals. Some seeds, such as those of the tomato

and blackberry, have impervious coats which enable them to survive

digestion in animals' stomachs; while others are suited for

transportation by water, by being buoyant and waterproof for long

periods of time.

Conditions Necessary for Germination

1. Preconditioning

Some seeds require specialized "pre-conditioning" before

they will germinate. Some examples include:

- alternate freezing and thawing may be required to break down and

crack hard shells

- a dormant period of "rest" in cool dry conditions may

be required by some seeds

- ponderosa pine seeds must be "singed" by the heat of

forest fires before they are able to germinate;

- the seeds of the Calvaria tree (native to Madagascar)

must be passed through the intestinal tract of turkeys before they

are able to germinate

- in the presence of red light and infrared light

some seeds, such as tomato seeds, are known to produce bioactive

chemicals called gibberellins (GAs) which promote seed

germination. In dicotyledenous plants (that is, plants whose seeds

have two embryonic leaves), dicots for short ,

such as the tomato, the GA promotes the growth potential of the

embryo and weakens the structures surrounding the embryo.

2. Moisture

Seeds tend to remain dormant as long as they are dry. Water softens

the seed coat and expands the protoplasm.

3. Oxygen

All green plants need oxygen to "breathe" or respire.

Like humans, they need oxygen to live and grow. However, dormant seeds

need little oxygen.

4. Warmth

- Minimum: Tomato plants will not germinate at temperatures

below 10°C.

- Optimum: Tomato plants germinate best between 17°C and

20°C.

- Maximum: Tomato plants will not germinate at temperatures

which exceed 35°C.

Germination

|

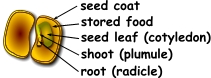

Seeds are protected by a hard shell or seed coat. This

shell can be extraordinarily tough. Some seeds require that

they be eaten by animals to soften the seedcoat and permit

germination. For others, simply soaking the seed in warm water

will soften the seed coat enough to allow the seed to begin to

germinate.

In nature suitable conditions are provided by climate and

weather. In agriculture the correct conditions can be

simulated in greenhouses and "hot beds".

|

|

|

|

Hidden inside every seed is a tiny embryonic plant complete

with root, stem and leaves, ready to sprout when suitable

conditions appear.

The seed's plant-parts are not "true" leaves,

stem and roots, but are effective enough to launch the plant

into its growth phase when true leaves, roots and stems

appear.

Flowering plants whose seeds have one embryonic leaf

(cotyledon) are called monocotyledons. Flowering plants whose

seeds have two cotyledons are called dicotyledons.

Tomato plants are dicotyledons.

|

|

|

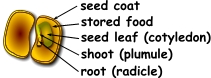

When warmth, water, and oxygen become available a seed

begins to germinate. The embryonic plant begins to grow and

the seed coat swells and breaks open under the pressure of the

growing seedling within the shell.

Before photosynthesis begins the spouting plant uses food

stored within the seed to grow.

As long as the environmental conditions remain favourable

the plant will continue to grow, the stem and the cotyledon(s)

pushing upwards and the root(s) extending downwards.

|

|

|

As the emerging seedling begins to grow its dependence on

stored food diminishes and the transition to its own

photosynthetic food production begins. It will not survive

unless ample light is added to the water, warmth, and oxygen

needed for germination.

|

|

At what point can we say

that germination has been successful?

In the Tomatosphere project we are dealing primarily

with tomato seed germination. Germination is, of course, a process

whose duration varies according to the type of seed and

the local environmental conditions to which the seed is

exposed.

Our interest is in both the rate (time), and the success,

of tomato seeds in the germination process.

|

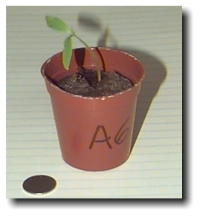

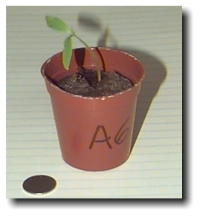

New tomato seedling

approximately one week beyond the "successfully

germinated " point. |

In order to ensure, as much as possible, the

self-consistency of all observations made by numerous

independent observers, the following criteria will be used to

define the condition "successfully germinated".

For purposes of this experiment, a seed can be

considered to have successfully germinated when two (2)

distinctly separate cotyledons (embryonic leaves) can be

seen.

|

|